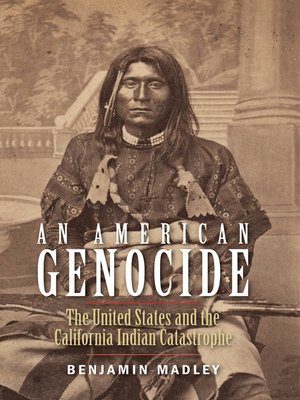

Benjamin Madley is an activist-historian specializing in Native America and colonialism in world history, famous for his work surrounding the systematic extermination of the California Indians which is compiled in his book An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe.

Madley professes that he became interested in the subject of relationships native peoples and colonizers at a young age. Growing up in a cabin near rural Redding, California, young Ben was acutely aware of the fact he was growing up in Karuk country, both in small tactile ways like finding arrowheads in neighbors fields and in deeper more troubling ones relating to his fathers’ work as a school psychologist and private therapist. “I saw firsthand at a quite young age this ongoing conflict between natives and newcomers… so at a pretty young age I began to think about what this meant, to colonize a place.” (Lawrence 8:38) These questions were only heightened upon his move to Los Angeles, where he began to wonder where all the native people were despite being in what he would later learn was the most densely populated Indian city in the western US.

“I began to wonder where everybody went and I began to study this history, and the further I went into it the more terrified I became by what I was seeing.” (C-SPAN 6:11)

What Madley was seeing was the horrific and systematic killing of thousands of Native Americans in California alone. The specific period of time he usually chooses to focus on (and the chronological setting of his book) is the time between 1846 and 1873, starting with the induction of California into the union and ending with the final large scale massacre of Native people. During this 27 year period, the Native American population in California dropped from 150,000 to 30,000, meaning that on average four of every five people died. While dislocation, starvation, and disease all played significant roles in the death toll, so did abduction, battles, massacres, individual homicides, and mass death in forced confinement on reservations. And rather than being the the wild urges of gold crazed invading settlers, much of the death was organized and paid for by civil and federal government, be it in the form of propaganda, donations of munitions, reimbursements for militia expenses, or actual troops in the field. All this evidence led Madley to an undeniably damning diagnosis for the period: Native Americans were being targeted by State-sponsored genocide.

While not everyone agrees with the definition of genocide as set forth by the UN in 1948, it is made exceptional by the mere fact that it was agreed upon unanimously and with no abstentions, as well as being the legal rubric utilized in the trials of war criminals associated with genocides in Rwanda and Yugoslavia. While the convention does not allow for retroactive prosecutions for crimes committed before its institution, Madley says that the naming of what the United States committed as a proper genocide is a powerful tool in honestly understanding what happened (Madley). While in recent years the U.S. school system has begun to require teaching on genocides like the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, and the Rape of Nanking, ideas of both Californian and American Exceptionalism have served to suppress the spread of the truth of the atrocities committed by the invaders against the Native Americans. In contrast, the required education California youth receive on the subject happens in the 4th grade, a fact Madley thinks is definitely intentional as “there is only so much of this horror, of this profound pain that you can present to a nine- or ten-year-old child.”(Lawrence 12:14)

Madley hoped for his book to accomplish a number of things in addition to a more robust education on the racial violence. ““You have this dark cloud of genocide, but at the same time you have this unbelievable story or resilience and survival.” (C-SPAN 9:45) In an effort to lay out the true scope of the Native Americans’ struggle, a large appendix of the book is dedicated to documenting every instance of killing Madley could compile. Despite the macabre premise, the section is very important to Madley, as he sees it as a memorial to all the lives lost, akin to the Yale Alumni War Memorial or Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial. He wanted a way to dignify the deaths of those otherwise largely forgotten to history. (C-SPAN 8:15) Moreover, he hoped the book would spark a wider dialogue as well as public discourse.

And for a while it seemed like would. Upon being published in 2016, An American Genocide met with widespread critical acclaim and received a cadre of awards. It was also publicly endorsed by Governor Jerry Brown, but the genocide was not officially recognized and named as such until 2019 when Governor Gavin Newsom issued a formal apology and is quoted as saying ““It’s called a genocide, that’s what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it, and that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books.” (Reuters)

Another way Madley’s work has an effect on the conversation of native rights and the postcolonial framework at large is the way it serves to complement and contextualize the works of others in the field. While An American Genocide may seem limited in scope of both region and time, what the people of America did in California between 1846 and 1873 serves as a call both to action and humility. Those of the far west have plenty to do and plenty to atone for, so when one picks up a book like Debora Miranda’s Bad Indians Madley’s work exists to remind us to approach with a humble heard and an open mind. While much of what he has taught is in the past, both its repercussions and the need for advocacy are very, very present.

Madley of course still feels there is much more work to be done, possibly by way of memorials and reparations. But it all begins with education, from the youngest Californian to the ones learning now from Madley himself, as he is currently an associate professor of history at UCLA. The work of an advocate-historian is never done.

Featured Photo by Library Foundation of Los Angeles

Works Cited

“Benjamin Madley – Associate Professor” Faculty Bios, UCLA History. Accessed 12/14/2020

“Benjamin Madley Speaks on Genocide of California Native Americans at Center for Advanced Genocide Research” USC Shoah Foundation, 2016. Accessed 12/14/2020

Lawrence, Sam. “It’s Time to Face our American Holocaust.” Grow Big Always, 2016. Accessed 12/14/2020

Slen, Peter. “An American Genocide.” C-SPAN, 2017. Interview. Accessed 12/14/2020

Madley, Benjamin.”‘The Savages were in Our Way’: California’s History of Genocide.” Truthout, Yale University Press. Chapter Excerpt. Accessed 12/14/2020

Reuters. “California Governor apologizes to Native Americans, cites ‘genocide.” Alarabiya, 2019. News Article. Accessed 12/14/2020.

Madley, Benjamin. An American Genocide. Yale University Press, 2016. Print.

Rothera, Evan “Book Review: An American Genocide by Benjamin Madley.” U.S. Studies Online, 2018. Review. Accessed 12/14/2020