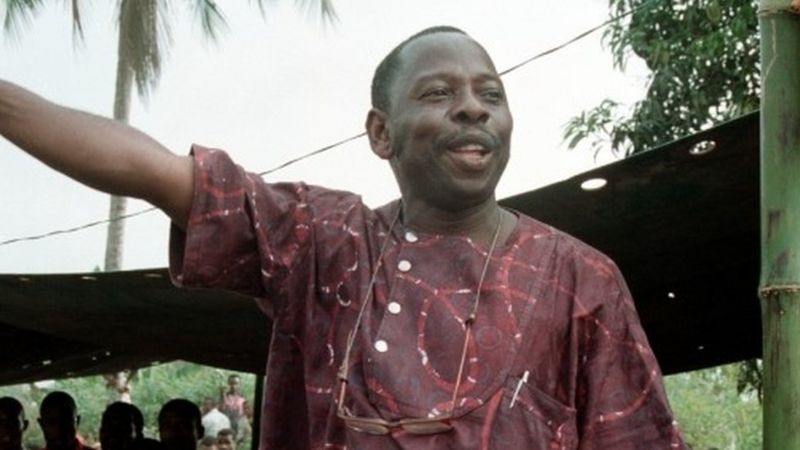

Ken Saro-Wiwa is among the most multi-faceted figures of modern African history. He filled a number of different roles throughout his livelihood, occupying himself as a scholar, educator, politician, business owner, play writer, journalist, author, TV show producer, political activist, and environmental activist. It is truly remarkable that Saro-Wiwa was able to apply himself successfully to such a diverse array of occupations. Unfortunately, a highly adept and versatile intellect is not always rewarded when harnessed against the will of powerful evils, and Ken Saro-Wiwa payed the ultimate price for dedicating his life to doing exactly that.

Ken Saro-Wiwa was born on October 10, 1941, in a southeastern Nigerian village called Bori. His family were members of the Ogoni tribe, a small ethnic minority in Nigeria that accounted for just 0.35% of the country’s population. The region of southeastern Nigeria occupied by this group is called Ogoniland, named after the local tribe. Ogoniland suffered severe environmental pollution from crude oil exploitation of the land, an issue that became close to Saro-Wiwa’s heart, and ultimately motivated much of his life’s work.

As early as secondary school, Saro-Wiwa distinguished himself as a passionate and accomplished student. He received departmental awards in History and English at government college of Umuofia, where he was also captain of a table tennis club. While attending University of Ibadan, he worked for the school’s drama troupe and wrote a play called Transistor Radio, which would serve as a foundation for his later creative works.

Saro-Wiwa began his professional life working as a teaching assistant at the University of Lagos. He also lectured English for a short period at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, when the Nigerian civil war of 1967-1970 broke out. Saro-Wiwa left Nsukka for his hometown of Bori upon news of the war, and shortly thereafter his stint in politics began.

After regrouping in his hometown, Saro-Wiwa moved back to Lagos with the intent to resume his teaching at the university, but was recruited into the federal war effort shortly after arriving. He left Lagos to serve as the federal government’s Civilian Administrator in Bonny, an Ogoniland city not far from his hometown of Bori.

While serving the federal government as Civilian Administrator, Saro-Wiwa began work on one of his better known novels, Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English. In this book, Saro-Wiwa reveals his own distaste for Nigeria’s political environment, writing of a main character who, like himself, gets recruited into the war effort on behalf of the military government, and finds himself disillusioned by the corruption and moral depravity he witnesses within the institution.

After the war’s end in 1970, Saro-Wiwa was appointed Commissioner of Education for the River’s State, a political jurisdiction of Nigeria that encompasses Ogoniland. After serving in this position for three years, he was ousted for advocating the Ogoni people’s plea for greater autonomy from Nigeria’s military regime.

This removal from office was essentially the end of Saro-Wiwa’s political career. With his new freedom from his duties as a public official, Saro-Wiwa took to business ventures in real estate and retail, through which he established wealth that provided him with the financial security to dedicate his efforts exclusively to creative pursuits and activism in his later years. He attempted to re-enter politics in 1977 by running for Ogoni Constituent Assembly representative, but lost in a close race.

The 1980s was a creative season for Saro-Wiwa, as he published a number of books in this decade, and aired Basi and Company (his most famous project) from 1985 to 1990. Most of his books from this era harken on similar themes he drew upon in Transistor Radio, commenting on societal ills of corruption and disparity through satirical humor. He continued publishing books in the 1990s, but with a different approach then those of the decade before; instead of using fictional satire to point out societal issues, he addressed these problems directly and analytically, presumably to inspire systemic change.

Saro-Wiwa’s shift in prose in the 1990s reflects a shift in his engagement with the environmental and political problems that had always provided him with a sense of existential purpose behind his pursuits. Rather than having an indirect impact on the issues he wished to address as he had previously done, in the 90s’ Saro-Wiwa fought these ills head-on. He became president of an Ogoni activist organization called MOSOP (Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People) in the early 1990s. This organization was built upon the agenda to accomplish three primary goals: increase Ogoniland’s autonomy from the military regime, restore Ogoni lands from environmental devastation, and receive a share of the profits generated from oil extraction taking place on Ogoni lands. These grievances were a response to contracts between environmentally irresponsible oil companies and the military dictator, whereby the military regime would receive large shares of the profits from the oil productivity.

In 1993, Saro-Wiwa and MOSOP orchestrated a massive peaceful protest of about 300,000 people, drawing international attention the plight of the Ogoni people and the malfeasance of the oil companies operating in the area. In response to pressures from bad press and generally damaged public relations, Royal Dutch Shell suspended their operations in Ogoniland, the repercussions of which would lead to the unjust execution of nine members of MOSOP.

On May 21, 1994, four Ogoni chiefs who happened to oppose MOSOP’s pleas for autonomy were murdered by unknown perpetrators, and Saro-Wiwa was arrested for conspiracy in the murders, along with eight other MOSOP leaders. Sani Abacha, the dictator who had recently lost a major source of revenue from his disrupted contract with Royal Dutch Shell, personally appointed four people to head a special tribunal to conduct the court proceedings with the dubbed “Ogoni Nine” MOSOP leaders. The case agains the “Ogoni Nine” was based primarily on two witness testimonies, and in spite of one of these witnesses confessing to having been bribed by Royal Dutch Shell for his original testimony, the court proceeded to charge the MOSOP suspects with inciting violence. They were publicly hanged on November 10, 1995. Saro-Wiwa was 54 years old when he was executed for his activism.

Ken Saro-Wiwa was passionate about a cause, and rather than ignoring the issues he saw gripping his world, he attempted to solve them with everything he dedicated himself to. He was a man with an existential purpose, using his highly competent mind to inspire positive change in various arenas, from politics, to entertainment, and eventually with direct activism. To those of us living in an era in which almost every aspect of life has changed due governing institutions’ responses to a supposedly profound threat, Ken Saro-Wiwa is an inspiration to individuals who feel the darkness of societal ills creeping ever further into the observable world. His example proves that instead of letting the negativity that too often arises from accepting dark truths weigh down one’s souls, one can harness such passions for the betterment of the collective good, finding purpose in opposing such darkness. For Ken Saro-Wiwa, the darkness he encountered was too gripping to ignore, so he fought it head on. In doing so, he lived a life of profound courage and existential meaning.

Works Cited

Pegg, S. (2000). Ken Saro-Wiwa: Assessing the Multiple Legacies of a Literary Interventionist. Third World Quarterly, 21(4), 701-708. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3993374

Doron, R. (2016, July 29). The Complex Life and Death of Ken Saro-Wiwa. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/07/29/the-complex-life-death-of-ken-saro-wiwa/

Olukoshi, A., Mustapha, A. R., Soyinka, W., & Mnthali, F. (1995, December). A Tribute to Ken Saro-Wiwa. Review of African Political Economy, 22(66), 471-480. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4006292.pdf