Distinguished as “the first Maori to publish both a book of short stories and a novel,” Witi Ihimaera has crossed oceans with his storytelling to bring the Maori experience out of the shadows. Almost single-handedly, Ihimaera has popularized Maori literature and, through his fictional and autobiographical work, helped create a place for Maori narratives in the world.

Born to Maori/Anglo-Saxon parents on 7 February 1944, Witi Tame Ihimaera-Smiler is a through-and-through New Zealander, having grown up mostly in Waituhi and Wellington. Waituhi, a Maori-dominated town just outside of Gisborne, drastically differs from Wellington, the pākehā (white)-dominated capital of New Zealand where Ihimaera moved as a young boy and felt challenged by his ethnic and cultural identity. Before graduating from secondary school in 1962, Ihimaera had transferred to three different schools, one of which was a Latter-Day-Saints boarding school. Ihimaera’s post-secondary education was just scattered, as he attended the University of Auckland for three years (1963-1966), did not complete his degree, and transferred to Victoria University, Wellington two years later to finally finish his B.A. in 1972. While at Victoria University, Ihimaera met Jane Cleghorn, a pākehā girl, whom he married on 9 May 1970. This relationship began a life of difficulty, given the racial tension surrounding mixed-marriages between Maori and pākehā people.

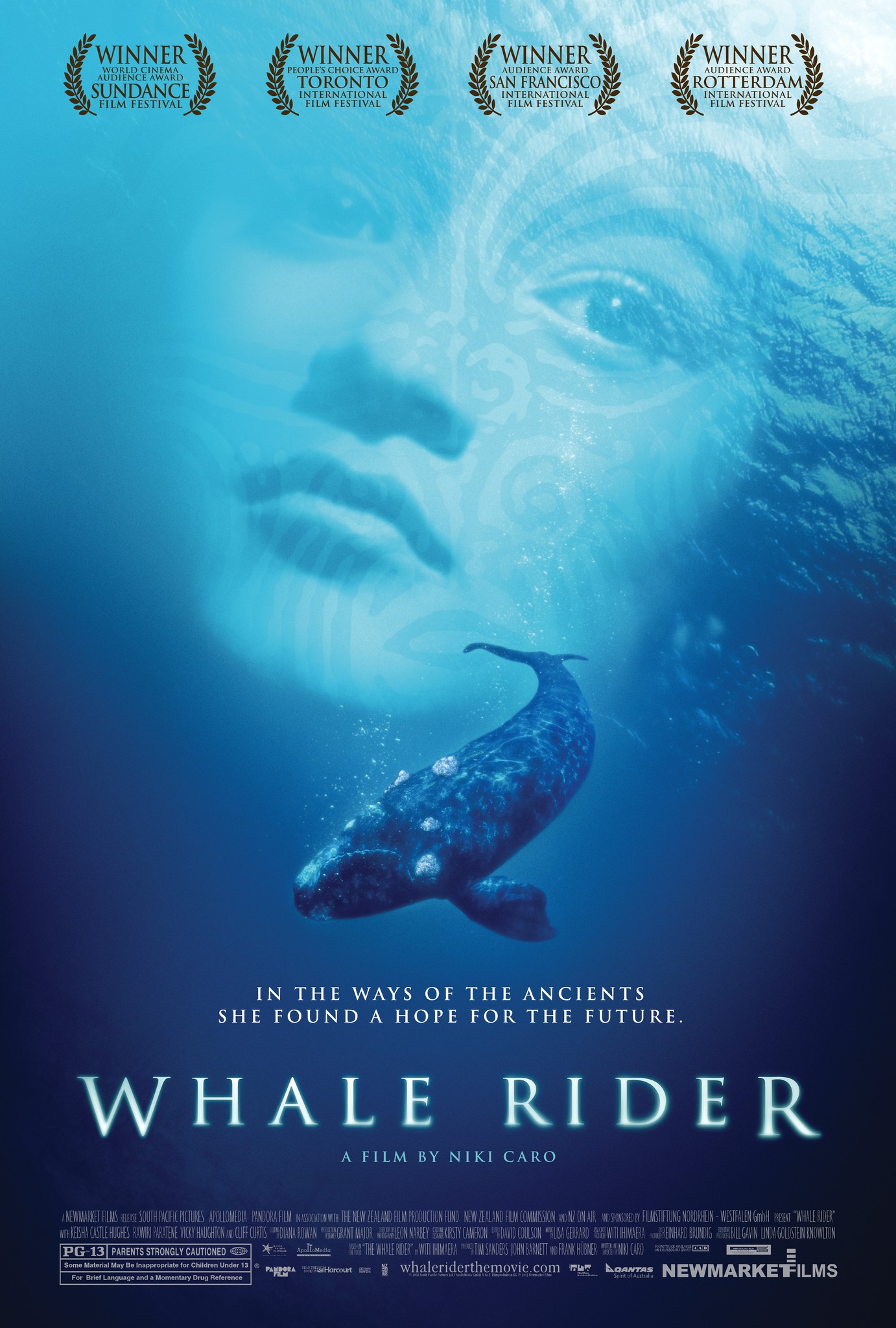

While in college, Ihimaera worked as a journalist and reporter for various publications, which allowed him to enter the literary world while creating and refining his own works. Just after graduating, Witi Ihimaera published his first collection of short stories called Pounamu, Pounamu (1972) that has become a staple text for elementary schools in New Zealand and has not been out of print since its publication — a print run of almost 50 years. Less than a year later, Ihimaera published Tangi (1973), his first novel. These back-to-back releases landed Ihimaera in the public eye and awarded him the honor of being the first Maori author to publish a collection of short stories and a novel. Not only were these works published, but they were well-received by the public and gained national fame and notoriety within international literary circles. After receiving his B.A., Ihimaera began his foreign policy career as an information officer, then as a secretary, then as the New Zealand Consul to the United States, and finally as the New Zealand Counsellor on Public Affairs to the United States. Stretching from 1973 to 1989, Witi Ihimaera’s career stint in international affairs lasted seventeen years, during which time he traveled all over the world and lived on the east coast United States in places like New York and Washington D.C. Although his day job demanded much of him, Ihimaera found time to write and published three novels, two short stories or collections of short stories, and various academic and promotional works commissioned by the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The most popular work of fiction during this time was The Whale Rider (1987), which was adapted for the silver screen in 2002 and nominated for many American film awards.

In 1990, Witi Ihimaera left his public career and began teaching and lecturing at the University of Auckland, a position he held for five years before taking on various fellowships and short-term teaching positions around New Zealand. While teaching, Ihimaera published one novel and one collection of short stories. The end of his teaching career is marked by the publication of his boldest work: Nights in the Gardens of Spain (1995). Although this novel is set in Europe and features a white male protagonist, the story is a veiled coming-out narrative that centers around the father of two girls who struggles with embracing his sexuality. While Ihimaera had written the story much earlier in recognition of his sexuality, he postponed publication in consideration for his two daughters. It didn’t take very long for the public to understand that the story was really about Ihimaera, himself, and the film adaptation made in 2010, entitled Kawa, was reset in New Zealand, which brought the story much closer to home than Ihimaera originally intended. With the release of this novel and the revealing of his sexuality, Witi Ihimaera and his wife remain married but stopped living together at this time. Ihimaera also left teaching to become a full-time writer, using his story and his international prestige to write the stories he felt needed to be written by and for Maori people.

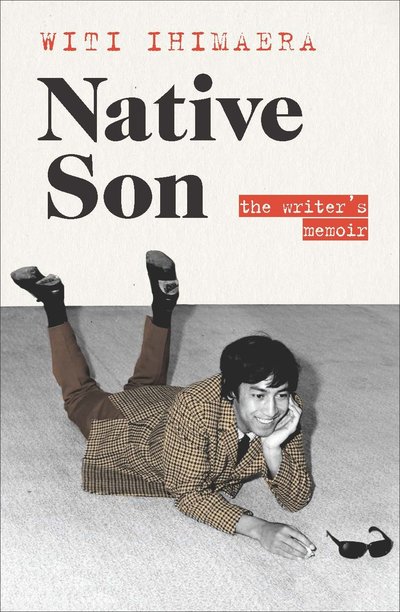

During his university career, Witi Ihimaera began editing Maori anthologies in order to bring the Maori experience into the wider public sphere, not just among niche literary circles. This work continued past his time at the University of Auckland, and though he lectures and speaks at various conferences and universities, Ihimaera has focused his energy on sharing raw stories and bringing Maori literature into a place of independence from pākehā recognition or influence. Instead of telling stories in contrast to the colonization of New Zealand or the decline of Maori culture in the face of modernization, Ihimaera has moved on to telling personal stories, beginning with the first in a series of memoirs called Maori Boy: A memoir of childhood (2014). In an interview in 1991, Ihimaera claimed that “The time may be coming when Maori will be writing from a less collective response and more of an individual response.” Though pākehā culture has left an indelible mark on Maori culture, Ihimaera seeks to push Maori authors out of the need to explain themselves and their experiences to others so they can merely write, like authors from dominating cultures who largely assume this privilege.

Witi Ihimaera’s most internationally-known piece, The Whale Rider (1987), is an exemplar of the kind of traditional and progressive work Ihimaera does that has developed Maori culture and literature as well as global understanding of colonized peoples. The Whale Rider is a story about Kahu, a young girl who remains the last descendant in a line of chiefs. Though she wants to serve her tribe and prove herself worthy, her grandfather is very traditional and refuses to show her affection because she is of no use to him unless she is a male. When a pod of whales beach themselves near the town, the tribe tries to save them, but it seems hopeless until Kahu reveals that she has the ancient ability to speak with the whales. This gift was last seen in the legendary Kahutia Te Rangi, the “whale rider” who brought the Maori people to what would become New Zealand. Using this ability, Kahu saves the whales and her grandfather’s stubbornness falls, restoring their relationship as Kahu becomes chief.

Though published relatively early in Ihimaera’s literary career, The Whale Rider exhibits the purpose and themes of Ihimaera’s works as a whole. In his respect for Maori culture, Ihimaera creates protagonists who are deeply connected to their familial roots and find the depth of their identity in their tribe. Any conflict in the novels largely stems from a tug or conviction, which the protagonist feels they are justified in following, that goes against traditional Maori values, which the protagonist also feels a desire to adhere to. These novels and short stories do not bring up questions of abandoning Maori culture, but finding one’s place within it and remaining loyal to it because it is life-giving for the Maori people. In this way, Ihimaera does not set pākehā culture and Maori culture against one another, but lovingly critiques and seeks to improve Maori tradition from within.

“My first priority is to the young Maori, the ones who have suffered most with the erosion of the Maori map, the ones who are Maori by color but who have no emotional identity as Maori. My second priority is the Pākehā (Non- Maori New Zealander) — he must understand his Maori heritage, must understand that cultural difference is not a bad thing and that, in spite of the difference, he can incorporate the Maori vision of life into his own personality. Thirdly, I write for all New Zealanders to make them aware of the tremendous value of Maori culture and the tragedy for them should they continue to disregard this part of their dual heritage.”

– Witi Ihimaera, “Why I Write” (1975)

At the same time, Ihimaera’s stories have brought Maori culture into the global theatre, clearly shown when The Whale Rider was adapted into film and nominated for many major awards. By sticking to his cultural values and traditions, Ihimaera sets himself apart from authors who try to appeal to a wider audience by neglecting their roots. In the trajectory of his published works, Ihimaera has brought Maori culture and literature to international attention, engaged with political and social conflict in a way that honors and challenges Maori culture, and worked tirelessly to encourage other authors to develop Maori literature past the road he paved. As Kahu took a risk and became the first female chief, Ihimaera has taken many risks to become the first published Maori novelist, beginning a literary tradition that has largely developed due to his initiative.

Cover Photo courtesy of Andi Crown via Penguin Books, New Zealand.

Works Cited

Chapman, Wallace. “Witi Ihimaera: life and influences.” Radio New Zealand, Sunday Morning, Interview, 1 July 2018. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/sunday/audio/2018651664/witi-ihimaera-life-and-influences.

Dekker, Diana. “Witi Ihimaera’s charmed life.” Stuff, 10 June 2013. http://www.stuff.co.nz/entertainment/8763358/Witi-Ihimaeras-charmed-life.

Farnsworth, Miles. “Shifting Indigenous Identities Through the Lens of Witi Ihimaera.” Miles Farnworth, Medium.com, 30 Aug 2018. https://medium.com/@milesfarnsworth/shifting-indigenous-identities-through-the-lens-of-witi-ihimaera-971d4bf432ef.

Ihimaera, Witi. “Maori boy: young Witi Ihimaera.” Newsroom, Excerpt from Native Son: the writer’s memoir, 2019. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/mori-boy-young-witi-ihimaera.

Ihimaera, Witi. “Native Son: the writer’s memoir.” Penguin Books. 2019.

Ihimaera, Witi. “Nights in the Gardens of Spain.” Penguin Books. 1995.

Ihimaera, Witi. “The Whale Rider.” Penguin Books. 1987.

Ihimaera, Witi. “Why I Write.” World Literature Written in English, Volume 14, Pages 117-119. 1975.

“Ihimaera, Witi (Tame).” Encyclopedia.com, Run by Cengage, https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/social-sciences-and-law/political-science-biographies/witi-ihimaera.

“Kawa.” Directed by Katie Wolfe, Performance by Calvin Tuteao, Cinco Cine Film, 2010.

Private Interview with Witi Ihimaera. Brigham Young University Archives. 1991.

“The Whale Rider.” Directed by Niki Caro, Performance by Keisha Castle-Hughes, South Pacific Pictures LTD, 2002.

“Witi Ihimaera.” The Arts Foundation. https://www.thearts.co.nz/artists/witi-ihimaera.

“Witi Ihimaera.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edited by Richard Pallardy. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Witi-Ihimaera.

“Witi Ihimaera.” Penguin Books New Zealand, Photo Courtesy of Andi Crown. https://www.penguin.co.nz/authors/witi-ihimaera.